Enter the experience

Skip the intro

In the history of the struggle against injustice

it is usually the faces of men

that are presented as heroes to the world.

But South African women

led mass campaigns and

went to jail for their protests.

Alongside their male comrades,

women endured unimaginable loss,

humiliation, detention, interrogation,

banning orders, house arrest

and murder

in their struggle for dignity,

equality and freedom.

They held families together

and laboured

to help communities survive.

They also supported

each other

in the struggle

against sexism

and patriarchy.

They found common ground

with all women

regardless of

race or class

and created non-racial organisations

long before the men did.

This is a small part of that

story of the courage and compassion

of South African women in the struggle

for freedom and democracy for all.

& THE WOMEN’S CHARTER

& THE ARMED STRUGGLE

& RIVONIA TRIAL

& THE FREEDOM CHARTER

TREASON TRIAL

1956 - 1961

After the Freedom Charter was adopted on 26 June 1955, the government arrested 156 participants and charged them with “high treason and a countrywide conspiracy to use violence to overthrow the present government and replace it with a communist state”.

The petitions of the Women’s March protesting passes in 1956 were used as evidence of this threat. The Treason Trial lasted nearly 5 years. All 156 were eventually found not guilty and released. Among those detained were leading women such as Lilian Ngoyi, Bertha Gxowa, Helen Joseph, Annie Silinga, Ruth First, Ida Mntwana, Sonia Bunting, and Frances Baard. FEDSAW and the ANCWL helped to organise support for the treason trialists and their families.

Treason Trial

TREASON TRIAL

Joseph

Helen Joseph’s close life-long friendship with Lilian Ngoyi was the most important contribution to her political education and her understanding of how apartheid’s policies of racial discrimination cruelly, deliberately, and disproportionally affected black women.

In her autobiography Side by Side, Helen recounts a particularly painful experience, when on 8 April 1960, she ‘celebrated’ her 55th birthday in the Women’s Section of Pretoria Central Gaol, where both she and Lilian were detained in separate wings. Their separation according to race left Helen feeling “so ashamed that I have a bed and get meat with my food, while Lilian has only a mat, blankets and gets mealie pap and boiled mealies.”

Helen’s friends outside sent her a birthday parcel that included tinned meats, chocolates, biscuits, liver sausage and spaghetti, which she wanted to share with Lilian. However, when the prison authorities visited her cell during rounds, Helen was expressly forbidden from sharing her gift with Lilian.This left Helen “embarrassed and unwilling to take any of it” herself. However, Helen’s wardress, Mrs Wessels, eventually convinced her to have some liver sausage, and this left her with a “great sense of guilt”. Helen considered her relationship with Lilian Ngoyi so important that she chose to be laid to rest next to her at Avalon Cemetery in Soweto upon her death on 25 December 1992.

Madikizela‑Mandela

Winnie Madikizela met her future husband, prominent anti-apartheid activist Nelson Mandela, at a time when she was enjoying success in her social work studies in Johannesburg.

After completing her degree in 1955, she was offered a scholarship in the USA, but because of her growing concern at the plight of Black South Africans, opted instead to take up a position as the first black medical social worker at the Baragwanath Hospital in Johannesburg.

Winnie and Nelson’s courtship and marriage developed against the backdrop of the 1956 Treason Trial, with Mandela a key defendant. In June 1958, they were married in Bizana, despite stringent government restrictions on Mandela’s movements.

Early married life proved to be increasingly turbulent, not only due to the ongoing trial (which spanned four years), or constant interferences by the police, or Mandela’s work as a lawyer, but also due to Winnie’s escalating involvement in the struggle.In October 1958, a pregnant Winnie was arrested after a mass action protest against pass laws. As further protest, the detained women would not apply for immediate bail, and eventually the ANC would raise money to pay for the fines.

Winnie lost her job at the hospital, and the trauma of incarceration sped up the birth of her daughter Zenani. “…Nomzamo, Zanyiwe meaning trial, I cannot believe my mother and father named me that, …Trial!?, why at the time a baby is born… what trial were they thinking of?... and then I spent all my life in the courts of this country on trial…”

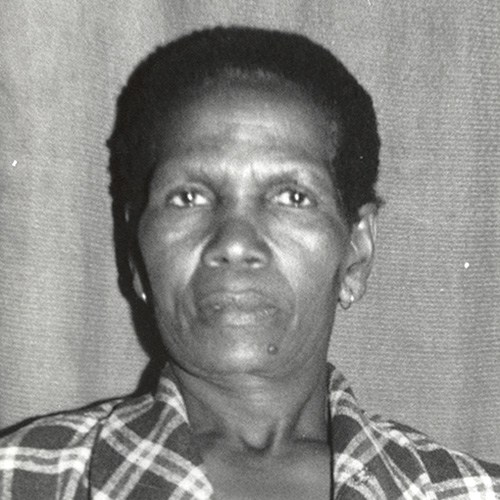

Mkhize

Nhlumba Bertha Mkhize’s relationship with the township of Inanda is deeply intertwined with her family history.

When Inanda Seminary was established in 1869, Bertha’s mother was one of the first pupils to attend the all-girls’ boarding school, the very first of its kind in South Africa.

Her mother’s experience at Inanda Seminary ensured her commitment to ensuring her children received an education.

She declared to her husband, “My children must be taught.I can’t know how to read the Bible and my children know nothing.

They must know more than I do.” At her mother’s behest, the Mkhize family moved back to Inanda after living in Esimahleni village, where Bertha’s paternal uncle served as chief.

Bertha was first educated at the historic Ohlange Institute, founded by Nokutela and John Dube, first President of the South African Native National Congress, which would later become known as the African National Congress.

Though Bertha was by then enrolled at Inanda Seminary, she enjoyed her time at Ohlange more because “they were better educated there because they were taught Algebra”, her favourite subject. Bertha also thought that Inanda was stricter and more disciplined than Ohlange.

In 1965, after the Durban City Council forced black-owned businesses like her tailoring business to move out of the city, Bertha returned to Inanda and established a creche at the Inanda Centenary Hall with assistance from the Seminary and funds raised in the community.

Naidoo

Manonmoney Pillay, known to her children and in the liberation movement as ‘Ama’ (mother), recalled her initial political involvement when she married Naransamy (Roy) Naidoo, a full-time activist with the Transvaal Indian Congress (TIC) in 1934: “…whatever meetings he goes to; I can be very busy, I had to go with him and my children, I must dress my children and go for the meeting.” Ama was imprisoned during the Indian Passive Resistance in 1947, then twice during the 1952 Defiance Campaign.

Motherhood gave new meaning to her own political expression and she committed herself to redefining her children’s future.

“We must not think of ourselves as housewives; we have to fight for freedom for our children; that is how we used to talk! I felt that we must fight for our freedom, to lead our children’s way. We want our children to be free; we were slaves; I don’t want our grandchildren to be slaves.” Owing to Ama’s hospitality and to her matriarchal disposition, the Naidoo home on Rocky Street in Doornfontein became known in the struggle as the ‘people’s house’.

During the 1956 Treason Trial, she was amongst the Defence and Aid Fund volunteers who collected food donations and catered for the trialists. All her children – Shanthie, Indres, Murthie, Ramnie and Prema – joined the movement, resulting in constant threats to and disruption of their family.

Nevertheless, Ama continued her political involvement as an executive member of FEDSAW, by participating in the Congress of the People in 1955, the Pretoria Women’s Marches of 1956 and 1963, and as vice president of the Transvaal Indian Congress upon its revival in 1983.

Naidoo

Having been shocked into awareness of the dehumanising effects of apartheid when she was ten, the 1956 Treason Trial and the arrests of 156 of South Africa’s foremost freedom fighters galvanised Durban-based teacher Phyllis into action.

Working alongside anti-apartheid activist Eleanor Kasrils, Phyllis collected money to support the Treason Trial accused and their families, as the accused could not work during the tedious court proceedings.

However, Phyllis believed that financial contributions were not enough, and secretly visited Chief Albert Luthuli in Groutville to request permission to form another ANC branch in Durban in 1957.

Luthuli countered that the party’s constitution only allowed black people to join the ANC, a decision that was overturned at the ANC’s 1969 Morogoro Conference.

In response to this, Phyllis, working with David Paton, the son of author Alan Paton, founded the Human Rights Society to work in tandem with the ANC.

Years later, Phyllis was excited to learn from Fatima Meer’s husband and fellow anti-apartheid activist, Ismail Meer, that Ayesha Dawood, a Muslim Treason Trialist from Worcester in the Western Cape, had been a full member of the ANC Worcester Branch since 1953!

Nyembe

Dorothy Nyembe had her first brush with the law while participating as a volunteer during the 1952 Defiance Campaign, and would be arrested time and time again thereafter, serving 15 years in prison from 1969 to 1984, the longest term imposed on a woman for a political ‘offence’ in apartheid South Africa.

She was widely recognised as a fiery leader of organisations such as the Natal Rural Areas Committee, ANC Women’s League (as chair of the Two Sticks branch committee), FEDSAW and uMkhonto we Sizwe.

Dorothy was one of the 18 women put on trial for high treason in 1956. "Mam D", as she came to be known, was not afraid to escalate the fight or push by any means to be heard.

In an interview conducted after her final release she said, “I know I will go back. I know I will die inside in jail, but I am not planning to remain and sit on my hands – no.” During a series of uprisings known as the Natal Women’s Revolts in 1959, she was at the forefront when groups of women armed with sticks and stones drove out beerhall patrons and vandalised and destroyed municipal infrastructure in protest against the criminalisation of traditional beer brewing, a significant vocation and income for many African women.

With a steadfast spirit Mam D stood against these increasing infringements of the freedoms and rights of African women. Even as she served her 15 year sentence, she maintained the same spirit, orchestrating a hunger strike in protest against the harsh conditions experienced by African women political prisoners in South Africa.

Silinga

Annie Silinga was a lioness of the struggle against apartheid, especially for the community of Langa in the Western Cape. A grassroots activist who established the first creche in Langa with fellow activist Winifred Seqwana, Annie was famously remembered for declaring that she would never carry a pass until Prime Minister J.G. Strijdom’s wife was required to carry a pass too (and by extension, all white South African women).

Annie’s magnetic presence, powerful oratory skills and unyielding defiance against the government’s attempts to control every aspect of her life inspired her fellow women activists to follow in her footsteps and resist the implementation of passes for African women at every turn.

Unsurprisingly, Annie was one of the leaders of the Women’s March to Pretoria in 1956.

However, Annie’s activism took a hefty toll on her and her family.

They were cruelly separated when Annie was deported from Cape Town to the Transkei in February 1956, despite having lived in the area since 1937.

Deportation and banishment were often used by the apartheid regime to exert its dominance over activists it had repeatedly failed to subdue through intimidation, harassment and even imprisonment.

This was especially true for Annie, as the state wrenched her away from her five children and her husband, Matthew, in an attempt to break her spirit. This attempt failed, as Annie successfully fought for her right to return to Langa, where she continued the struggle against apartheid until her death.

When we discourage dissent and protest, we cripple democracy. How can we ensure that our citizens are always allowed to speak truth to power without fear and intimidation?

Difference is often silenced by labelling it as criminal, sick, insane or evil. How do we ensure that diverse voices are valued – in our homes, schools, places of worship, businesses, courts, parliament, and the press?

DEFIANCE CAMPAIGN

1952

In 1952 the ANC, together with the Congress Alliance (a partnership between the white Congress of Democrats, the South African Indian Congress and the Coloured People’s Organisation), launched a country-wide campaign in which activists openly defied unjust apartheid laws.

They walked through ‘whites only’ entrances, sat on ‘whites only’ benches in parks and refused to carry their passes. Women played an important role. In the Eastern Cape, for example, 1 067 out of the 2 529 activists were women. The police responded with extreme violence. More than 8 000 people were arrested, and amongst them hundreds of women. The Defiance Campaign strengthened the women’s movement.

DEFIANCE CAMPAIGN

DEFIANCE CAMPAIGN

Dawood

Ayesha Dawood held the distinction of being the only non-African card-carrying member of the ANC until the 1980s when party membership was opened to all races. She was also the only Indian woman accused of high treason in 1956. This is largely due to the instrumental role she played in mobilising and politicising the people of Worcester in the 1950s. Ayesha became formally involved in political work from the time that she volunteered as an organiser during a one-day strike on 7 May 1951 to protest attempts to remove Coloureds from the Common Voter’s Roll. Meeting Ray Simons of the Food and Canning Workers’ Union was the beginning of her political journey. Ayesha became the secretary of the Worcester United Action Committee, which coordinated political action in the area, and was on the local organising committee during the Defiance Campaign of 1952.Ayesha represented South Africa at a conference of the Women’s International Democratic Federation in Denmark in 1953 and represented the ANC at the World Peace Conference in Budapest, and the World Youth Congress in Bucharest. When she returned, Ayesha addressed her first public meeting of the ANC, and called for unity across racial lines. For telling the meeting, ‘We want nothing from the white man, only our right,’ she was charged under the Suppression of Communism Act.

Du Toit

The movement of women trade unionists was never about individual struggles for freedom and equality. Bettie du Toit, a rare white Afrikaans-speaking woman in this movement, embodied the collective struggle for human dignity by actively defying inhumane laws and encouraging others to proudly demand their human rights.

Through her affiliations with various trade unions such as the Textile Workers’ Industrial Union and the Transvaal and Natal Canning Works, she steadfastly stood for the welfare of workers.

After she was banned for life from any trade union work as a consequence of her participation in the Defiance Campaign in 1952, Bettie would continue to defy apartheid laws in solidarity with those gravely affected by their injustices, among others by protesting the Asiatic Land Tenure Act (Ghetto Act).

Bettie also secretly ran Kupungani, a welfare organisation she started in Soweto, which constantly placed her at risk of imprisonment by the apartheid regime. While in exile in Ghana, she lost her eyesight after contracting Stevens-Johnson Syndrome. This prompted a move to London, where she taught herself braille. Bettie dedicated herself to teaching this skill to others until she returned to South Africa in 1993.

Gxowa

Bertha Gxowa quickly proved her mettle as a fearless freedom fighter when she joined the struggle against apartheid at 22. Described by Helen Joseph as being ‘tall, bespectacled and lively’, Bertha and fellow Treason Trialist Helen formed a close friendship when they worked closely together as national organisers of the 1956 Women’s March to Pretoria.

As an unmarried woman at the time, Bertha was free to accompany Helen into African townships to garner support for the march, where Bertha’s intimate knowledge of the backstreets allowed them to remain undetected by the police. However, their stealthy township campaigns were nearly compromised one night when Helen almost ran over a black policeman.

As the policeman approached to apprehend them, Bertha turned to Helen and jokingly said, “You nearly kissed him!” She then took charge of the situation by coaxing the officer into letting them go.

Bertha and Helen also travelled with Robert Resha and Norman Levy on a campaign spanning 6500 km across the length and breadth of South Africa to recruit women to join the Women’s March to the Union Buildings.

Mafekeng

Elizabeth ‘Rocky’ Mafekeng was admired for her advocacy as a trade unionist.

She rose up the ranks and held executive positions in organisations such as the African Fruit and Canning Workers’ Union (AFCWU), the Federation of South African Women (FEDSAW), the African National Congress Women’s League (ANCWL) and the South African Congress of Trade Unions (SACTU). In 1959, the apartheid regime banished Elizabeth from her home of 32 years in Paarl and from her husband and their 11 children, to a desolate and unfamiliar farm in the Vryburg district, 1125 km away.

She was one of the first women to be banished under the Native Administration Act of 1927 though the government could present no concrete grounds for it.

There had been no trial or public hearing, and therefore no possibility of an appeal. The story came to be known as the ‘Mafekeng Affair,’ and made international headlines.

The public anger at Elizabeth’s banishment led to the first large-scale AFCWU riot in the Western Cape. However, Elizabeth escaped to Lesotho with her baby Uhuru shortly before her scheduled deportation.

During her years in exile she lost her mother and husband, but it was too risky to attend their funerals. Elizabeth would only return to South Africa after the unbanning of all opposition political formations in 1990.

Matomela

Florence Matomela, a leading figure in mobilising women to participate in the Defiance Campaign in 1952, was known by her community of New Brighton as “always leading and drawing others to her side”.

Her best friend and life-long comrade in the struggle, Frances Baard, remembered Florence as “always laughing, warm and generous of heart”. Florence and Frances went through many significant events together, including the Defiance Campaign, the Treason Trial, and long-term detainment as political prisoners.

According to Frances, Florence also possessed a fiery, defiant nature that delegates from all over South Africa witnessed at the inaugural FEDSAW conference at the Trades Hall in Johannesburg on 17 April 1954. Florence, as part of the Eastern Cape delegation, was set to speak during the later stages of the conference, along with a number of other women.

Helen Joseph described Florence as “unforgettable, as she strode to the platform to speak”. When chairwoman Ray Alexander warned that she should only speak for three minutes, Florence stood tall, folded her arms and said, “I am a defier! I shall speak for as long as I like!”

Both Helen and Frances confirmed. In their autobiographies that Florence spoke for longer than three minutes!

Shope

As the struggle for liberation was forced underground after the Sharpeville Massacre, cadres were secretly recruited to leave South Africa. At the age of 29, Gertrude Shope left teaching to participate in a campaign to boycott Bantu Education.

She also joined the ANC at this time. After serving as chairperson of the ANC Women’s League Central Western Jabavu branch, and provincial secretary of FEDSAW, and given her increased participation in political activities, Gertrude was encouraged to leave South Africa and join her husband Mark in exile.

They served as representatives of the ANC whilst raising their children in Botswana, Tanzania, Czechoslovakia, Zambia and Nigeria. Cultural assimilation may have become a norm for the Shope family, but their focus remained on fighting for freedom in South Africa.

As part of the ANC’s Women’s Section in Tanzania, Gertrude focused on the representation and support of women in international solidarity. Importantly, the ANC Women’s Section formed a secretariat that guided all women’s activities through collective help desks.

These help desks tackled issues pertaining to health, children, education, logistics, and finances.

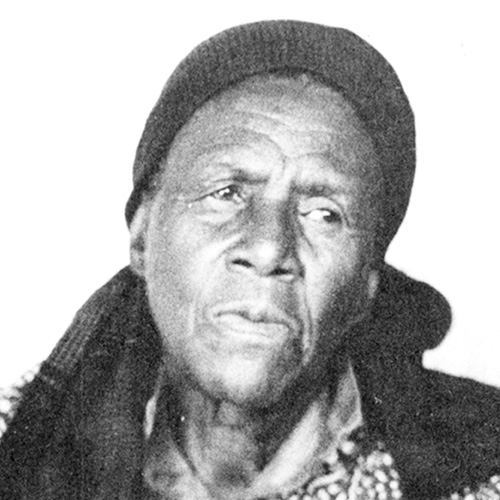

Tamana

Dora Tamana is well remembered as one of the fiercest and most vocal opponents of apartheid during the 1950s and 1960s. However, her home life was constantly beset by tragedies, largely inflicted by the apartheid regime.

In 1921, Dora’s life irrevocably changed when her father, two uncles and her future husband John were victims of the Bulhoek Massacre in the then Transkei. Though John survived, her father and uncles were among 163 Xhosa people murdered by the police.

In 1930, Dora and John moved to Blouvlei in Cape Town in an attempt to move past their shared trauma, provide a better life for their young children and establish a more permanent home.

Dora was one of the first people to erect a shack in the Blouvlei area, which she painted white.

Her home also served as the site for Blouvlei Nursery School, which she established in 1955 and is still operating today.

Dora’s dream of a stable, permanent family home was repeatedly destabilised by the apartheid regime through traumatic forced removals legally enforced by the Group Areas Act.

However, Dora resiliently rebuilt her home every time, which inspired many around her to do the same.

What privileges are you willing to risk to create a more just and equitable society for all?

Are you willing to speak out against prejudice and discrimination, even if that costs you family relations, friendships and threatens your job?

Are you willing to ensure your voice is heard, even if that means challenging established tradition or performing acts of civil disobedience that may lead to your arrest?

What is the price of your silence and inactivity?

FEDSAW & THE WOMEN’S CHARTER

1954

In 1954, The Federation of South African Women (FEDSAW) was created as a non-racial women’s movement. At their first conference, all the catering was done by men to give women more time to debate political issues.

FEDSAW adopted a Women’s Charter, which called for the right to vote; equality of opportunity in employment; equal pay for equal work; equal rights in relation to property, marriage, and children; and “the removal of laws and customs … which have the effect of placing wives in the position of legal subjugation …” The Women’s Charter further demanded paid maternity leave, childcare for working mothers, and free and compulsory education for all South African children.

FEDSAW & THE WOMEN’S CHARTER

FEDSAW & THE WOMEN’S CHARTER

Abrahams

Elizabeth Abrahams rose to prominence as one of the leaders of the Food and Canning Workers’ Union (FCWU) in the Western Cape during the mass anti-apartheid trade union campaigns of the 1950s and 1960s.

Fluent in Afrikaans and English, Elizabeth provided a critical bridge between the largely Afrikaans-speaking workers in the factories the FCWU represented, and their English-speaking committee members and her FEDSAW colleagues like Ray Alexander, Frances Baard, Elizabeth Mafekeng and Mary Moodley.

Along with the aforementioned women, Elizabeth was credited for “typifying the militant spirit of the FCWU during the 40s, 50s and 1960s. Deeply committed women, they sacrificed a great deal to devote their lives to the struggle of the works and people of South Africa as a whole”.

During Elizabeth’s term as Acting Secretary General from 1956 to 1964, the FCWU was the only political organisation in South Africa that could claim that all of its secretary generals and over 50 percent of the management committee were women.

This is especially impressive when one considers that FCWU leaders like Ray Alexander, Frances Baard and Elizabeth Mafekeng were banned from participating in trade union activities by the apartheid regime.

Elizabeth’s determination to keep women’s voices at the forefront of the trade union movement would result in her being banned for five years by the apartheid regime in 1964.

Alexander

Born in Varakļāni, Latvia, Rachel Alexandrowich became active in the underground cells of the Latvian Communist Party from the age of 13.

Her mother became fearful of what might happen to her after she was nearly arrested for attending a ‘masofka’ (an illegal gathering).

It was decided that Rachel should join her siblings, Isher and Deborah, who had emigrated to Cape Town, but that she should undergo underground training before her departure.

Days after arriving in South Africa in 1929, Rachel joined the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA), and her co-workers at True Bothers nicknamed her ‘Ray’.

She also began her life’s work of organising and mobilising black and white workers to form trade unions to enable them to demand better working conditions.

In this work, Ray recognised the difficult working conditions women endure in factories, in particular harassment and gendered wage disparity. In 1951, she was listed under the Suppression of Communism Act and subsequently banned from participating in trade union activity.

Undeterred, Ray continued her work underground.

Inspired by the Women’s International Democratic Federation (WIDF) formed in Europe after WWII, she decided to help establish a similar organisation for all South African Women.

In 1953, Ray proposed this idea to different women’s organisations, notably at a secret meeting with Florence Matomela and Frances Baard in Gqeberha. With the resolution authorised, she continued working towards the launch of the Federation of South African Women.

On 17th April 1954, Ray opened the Women’s Conference at the Trades Hall by saying, “all of us are here because we want to find solutions to the problems which we women have so much at heart...”

Baard

Frances Baard’s ability to inspire confidence and courage in the women of New Brighton, Gqeberha, was essential to FEDSAW becoming a reality. In 1953, Frances, with fellow trade unionist, comrade and best friend Florence Matomela organised a meeting between 50 women from the area and trade unionist Ray Alexander, who was visiting from Cape Town.

The women of New Brighton discussed their anxieties around the looming threat of passes for black women, pitifully low wages, and increasing rent, food and transport prices in the area.

It is believed that Frances suggested that Ray Alexander should consider organising a national women’s conference, inviting all South African women to attend. The inaugural FEDSAW national conference was held at the Trades Hall in Johannesburg on 17 April 1954.

Frances and others travelled from Port Elizabeth and East London to the conference by car, which was unusual at the time, as the long journey north was considered too dangerous and expensive for women.

With fellow activist Connie Njongwe at the wheel, the group of women almost missed the conference when the car broke down on the way. Frances was “scared that we should not get there”, but luckily they arrived in the nick of time and made a dramatic entrance at the Trades Hall.

Frances remembered that “they were all in traditional dress, long ochre skirts and headdresses, and that whole conference stopped… they turned to look at us, such a group, looking so good!”

Bernstein

Following the Sharpeville Massacre in 1960, Hilda Bernstein was among many women who were detained without charge under the State of Emergency.

In 1953, Hilda had been banned from participating in 26 organisations and from writing or publishing anything related to her public political activity as a member of the South African Communist Party (SACP).

Hilda, described by Ray Alexander as “a committed feminist and an eloquent recorder of the liberation struggle” was a founding member of FEDSAW in 1954, where she helped draft the Women’s Charter.

Hilda was an avid illustrator, and frequently added entertaining drawings to the letters she wrote to her four young children whenever she was in detention.

Famously, Hilda also produced sketches (now the only remaining visual accounts) of what transpired inside the Palace of Justice during the Rivonia Trial between December 1963 and June 1964.

Her husband Lionel ‘Rusty’ Bernstein, as one of the accused, was acquitted and the family soon escaped on foot to Botswana.

The Bernsteins eventually settled in Britain where Hilda continued her role in the struggle against apartheid as part of the ANC External Mission, the Women’s Section, and the Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM).

Hilda later established herself as an accomplished author, publishing The World That was Ours in 1967 to great acclaim, and as an artist with notable works included in private and public collections across the world.

Meer

The advent of the Treason Trial in early December 1956 was a stressful time for Fatima Meer. Her husband Ismail, leader of the Natal Indian Congress, was recuperating at his in-laws’ home at 84 Ritson Road after an appendectomy.

On the morning of 5th December, the police raided the house and named Ismail one of 156 people accused of High Treason by the apartheid regime.

Fatima acted quickly to remove any incriminating documents. She recalled in her memoir, “I grabbed my chance and dashed to the Umgeni Road house to clear and secure as many of our papers as possible from the police.

I was certain that after arresting Ismail, they would raid the house. I felt a sense of victory as I moved whatever I could into the house of our immediate neighbours, the Mangals.” Returning to her parents’ house, Fatima found Ismail’s physician Dr Davidson arguing with the police who demanded to detain her husband despite his ill health.

Forced to comply with Dr Davidson’s orders, the police arranged a constant guard outside Fatima and Ismail’s bedroom to ensure he could not escape.

When Ismail was taken into custody to join the other Treason Trialists at the Old Fort Prison in Johannesburg, Fatima was left alone with her small children.

She recalled: “My life, at age 28 was suddenly full of newfound responsibilities which included caring for the children, running the home, looking after Ismail’s office (or at least keeping an eye on it), working out ways to curb household expense, looking for some employment and over and above this, supervise the building of our new home.”

Palmer

As one of the first women to join the CPSA, Josephine Mpama (Palmer) was active in political campaigns since the late 1920s, promoting community struggles that challenged the daily lives of Black people.

She notably mobilised the people in her hometown of Potchefstroom against the government’s ‘lodgers permits’, which sought to undermine the stability and cohesion within Black families.

Where ANC narratives often dominate South African liberation struggle history, Josie’s political life offers a different perspective. The Communist Party was her primary political home.

She travelled to Moscow in 1935 for training with Communist International (Comintern), disguised as Mathilda First’s nurse, and under the pseudonym ‘Red Scarf’.

When the Party was on the brink of collapse in the 1930s, she took a strong stance to protect it, facing stiff internal opposition.

Later, demonstrating their support for autonomous organisations for women, Josie and Madie Hall-Xuma founded the Zenzele clubs, non-political women’s clubs that encouraged women to learn new skills and hobbies that would enable them to earn a living.

Though its members were initially attracted by the idea of survivalist activities, it was also through organisations such as Zenzele that FEDSAW was able to rally women to their common goal.

Josie was also a leading figure in the formation of FEDSAW before she received banning orders in 1955 and was detained under the State of Emergency in 1960.

Thereafter Josie withdrew from politics due to health challenges caused by osteoporosis; however, she remained devoted to the Anglican Church, to various women’s groups and remained an active presence in her neighbourhood, sharing her knowledge of Afrikaner folk medicine to treat illnesses.

Ngoyi

Lilian Ngoyi typified the relentless and militant revolutionary spirit of anti-apartheid women activists in the 1950s and 1960s. In 1955, Lilian and Dora Tamana were invited to represent FEDSAW at the World Congress of Mothers in Lausanne, Switzerland.

Hosted by the WIDF, the congress was viewed as the perfect opportunity for Lilian and Dora to highlight the hardships endured by black women back home, and forge new links with other women’s organisations from around the world. As they had not received passports nor permits from the apartheid government, due to being ‘radically political blacks’, Lilian and Dora, with organisational assistance from Ray Alexander and Hilda Bernstein, attempted to get from Cape Town to Europe by sea. However, they were thwarted upon being discovered passport-less. Undaunted, Lilian and Dora then flew to London from Johannesburg, where according to Lilian “they encountered hostile looks and whispered comments from the passengers. Then, the captain announced that this was his plane and that there would be no apartheid on board as all his passengers were equal”. After a few weeks in London, Lilian and Dora went on an eight-month sponsored tour of the Soviet Union, Hungary, Romania, and the People’s Republic of China. Upon their return to South Africa, Lilian remarked to Helen Joseph that “it was bitter for them to come back from many lands where, for the first time in their lives, they had been treated as human beings and honoured leaders of their people. Now, they had returned to the land of their humiliation”.

Which women’s groups, associations and networks do you stand in solidarity with? How is the collective intelligence of those women being harnessed and expressed through action?

How do you let women who are in crisis know that your support and resources are available to them?

What is the status of women’s movements in South Africa today?

What continues to distort, dilute, and silence the voices of women?

How can agency and solidarity be nurtured?

CONGRESS OF THE PEOPLE

& THE FREEDOM CHARTER

1955

The Congress of the People was the biggest non-racial gathering ever held in South Africa at the time. For months male and female volunteers (amavolontiya) had visited homes, farms and factories collecting the demands of ordinary South Africans.

These ideals were summarised in the Freedom Charter that outlined the shared vision of a democratic and non-racial South Africa. In the shadow of armed police, it was defiantly accepted by jubilant crowds in Kliptown, Johannesburg on 26 June 1955. Helen Joseph and Josie Mpama read the demands made by women. The Federation of South African Women (FEDSAW) arranged accommodation for the more than 2 000 delegates.

CONGRESS OF THE PEOPLE

& THE FREEDOM CHARTER

CONGRESS OF THE PEOPLE

& THE FREEDOM CHARTER

Bunting

Sonia Bunting dedicated her life to the struggle against apartheid from an early age. Her parent’s experience of anti-Semitism in Eastern Europe and the growing global turbulence of the 1940s influenced 20-year-old Sonia to join the CPSA in 1942. At the time, she was enrolled as a medical student at the University of the Witwatersrand, but soon abandoned this in favour of following her passion- working fulltime at the Communist Party offices where she met her husband, journalist, and fellow comrade Brian Bunting.

The couple married in 1946, relocated to Cape Town, and continued their political activities which intensified after the National Party won the general election in 1948, codifying apartheid as law. Following the implementation of the Suppression of Communism Act in 1950, the couple took charge of The Guardian, later renamed The New Age, a left-wing newspaper.

Sonia frequently wrote articles criticising the oppressive apartheid regime, while Brian served on the paper’s editorial board. Sonia’s work at The Guardian introduced her to other white women left-wing activists like Ruth First, Helen Joseph, Jacqueline Arenstein and Yetta Barenblatt, whom Sonia regarded as ‘high-powered, well-informed, primarily ideologically committed leftists.’ In 1955, Sonia’s ardent resistance of apartheid resulted in her being invited by the Congress Alliance to speak at the historic Congress of the People in Kliptown, where the Freedom Charter was also developed. Following this, Sonia was charged with high treason during the nationwide arrests of prominent Congress Alliance members on 5 December 1956.

Sonia was flown to Johannesburg and detained in the Women’s Section of the Old Fort Prison, where she was soon joined in a cell by Ruth First, Helen Joseph, Jacqueline Arenstein and Yetta Barenblatt, also accused of high treason.

Cachalia

Amina Cachalia’s sister, Zainab Asvat, ten years her senior, greatly influenced Amina’s political development and was considered a remarkable trailblazer and a formidable anti-apartheid and women’s rights activist.

Zainab was the first Muslim girl to attend high school in the Transvaal and later became the first Muslim woman to become a doctor in South Africa. Zainab also shared with Amina the many political lessons she had learned from their father, E.I. Asvat, a dear friend of Mahatma Gandhi, who took Zainab to Transvaal Indian Congress meetings when she was a young girl. Zainab participated alongside Dr Kesaveloo Goonam and Prof Fatima Meer in the Indian Passive Resistance Campaign in Durban in 1946. Amina, a student at Durban Indian Girls’ High School at the time, desperately tried to join the campaign but was forbidden as she was seen as too young. According to Amina, Zainab’s arrest during this campaign was the ‘spark’ that confirmed that she too ought to join the struggle. As members of FEDSAW, Amina and Zainab both participated in women’s marches to the Union Buildings on different occasions. Amina, heavily pregnant at the time, was present as 20 000 women marched to Pretoria in 1956, where she was poised to replace Rahima Moosa on the frontline if Moosa were arrested. In December 1963, Zainab organised a march of 2000 women protesting against the Group Areas Act to the Union Buildings, where the apartheid police met the women with violence.

First

Ruth First was introduced to socialist politics at a young age by her parents, Julius and Tilly First.

Their encouragement inspired her vocal commitment to the struggle against apartheid and other social injustices. Social investigation was a necessary part of her life’s work, shown by her commitment to challenging, researching and explaining socialist and leftist ideologies, whether as a member of the Left Book Club, a debater at Florian’s Café, 13 Kholvad House, a speaker at conferences, a lecturer, mentor and journalist. She is remembered for her boldness and style, but her true strength lay in her role as a political activist and educator, and her ability to inspire connections between ideas and actions by constantly questioning and challenging herself and those around her. Ruth made a profound impact on her colleagues, comrades and students, and as such became a target of the apartheid regime. In August 1963, shortly after the start of the Rivonia Trial, she was arrested and detained for 117 days under the 90-Day Act. Ruth, like too many in the liberation movement, paid the ultimate sacrifice when she was assassinated by the apartheid government in Maputo in 1982.

Mkhize

Florence Mkhize, like many people, decided to be part of the solution to South Africa’s problems by joining the liberation movement at a young age.

She came to the forefront of the struggle as a volunteer during the 1952 Defiance Campaign, and this led to her first banning shortly afterwards.

Following in her aunt Bertha Mkhize’s footsteps, ‘Mam Flo’, as she was better known, became a seamstress whilst also remaining politically active. She often used her workplace, a sewing factory in the Lekhani Chambers, for meetings with her fellow comrades.

As a volunteer during the formulation of the Freedom Charter she was tasked with mobilising people to contribute.

However, she missed the Congress of the People in Kliptown as her bus was stopped by the police and forced to return to KwaZulu-Natal. ‘Mam Flo’ continued her political work as a founding member of FEDSAW and was instrumental in the organisation of the 1956 Women’s March to Pretoria.

She tirelessly spoke out against the pass laws and tried numerous times to meet with the Chief Native Commissioner of KwaZulu-Natal, who refused to give her an audience.

Mam Flo was arrested for the first time along with 622 women during an anti-pass protest. In 1967, Ranjith Kally photographed Florence burning her passbook in defiance of the unjust laws and its oppressive symbolism.

This photo was widely distributed, and though it encouraged others to join the campaigns, it also made Florence a recognisable target to the police.

Mntwana

Ida Fiyo Mntwana became active in politics in 1927 when, as a dressmaker, she joined the Industrial and Commercial Workers Union, the first general workers trade union to include black workers from all industries since its establishment in 1919.

After Madie Hall Xuma resigned as President of the ANCWL in 1949, Ida took over the position.

Like Lilian Ngoyi and other members of the more radical ANC Youth League, Ida was eager to turn the ANC into a mass movement and increase the participation of women in the struggle.

She encouraged women to take part in demonstrations, strikes and other acts of civil disobedience. This commitment to the struggle led to Ida being elected onto the ANC Executive Committee during the 1950s, and being elected as the first president of FEDSAW.

She led many women’s anti-pass demonstrations through the 1950s, including the 1955 march to the Union Buildings. Under her leadership, FEDSAW drafted a Women's Charter, which informed the Freedom Charter at the Congress of the People in June 1955.

On the second day of the Congress, police tried to incite a conflict between themselves and the delegates.

Ida calmed the crowds by singing freedom songs and the Congress was able to continue. In 1956, Ida was also one of the defendants in the Treason Trial, but charges against her were dropped in 1958.

Moosa

Rahima Moosa and her twin sister, Fatima Seedat, were alike in many ways. Raised in a liberal and politically conscious Muslim household, their father introduced the twins to the teachings of Satyagraha and Marxism, with the latter influencing Fatima to join the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA) and Rahima to serve as the Cape Town branch leader of the Food and Canning Workers’ Union.

The twins also married into politically active families – Rahima marrying fellow comrade and Treason Trialist Dr Mohammed ‘Ike’ Moosa; and Fatima marrying fellow communist and secretary of the CPSA, Dawood Seedat.

When they were 34 years old, Fatima and Rahima, who was heavily pregnant at the time, both participated in the Women’s March to the Union Buildings on 9 August 1956.

The twins used their identical looks to great effect – the security police often had great difficulty in telling Rahima and Fatima apart, and they would evade the police by switching identities when one of them was in trouble.

In the 1960s, Rahima and Fatima were both banned under the Suppression of Communism Act, and in later years both suffered from diabetes, which resulted in Rahima’s death in 1993 and Fatima’s death ten years later, in 2003.

Resha

Magdaline ‘Maggie’ Resha was a fiercely outspoken critic of the apartheid regime.

She was one of the first black women to receive higher nursing training at Holy Cross Hospital in Flagstaff, Eastern Cape, and recounted that “several black nurses were often given only a Hospital Certificate, and not allowed to take State Registration, because their standard of education at entry was considered to be very low.”

Her political education also started at Holy Cross, when she read about the ANC in an old copy of Bantu World. After qualifying in 1946, Maggie worked at Pretoria Hospital and experienced the discrimination of the healthcare system first hand. Black nursing staff were grossly underpaid, worked long hours and suffered dehumanising racism at the hands of their white colleagues.

This experience, along with marrying militant ANCYL activist Robert Resha in 1948, and joining the ANC and FEDSAW, entrenched her commitment to the struggle against apartheid.

In 1958 Maggie led an anti-pass demonstration to Baragwanath Hospital after the South African Nursing Council required black nurses to sign a race classification register and carry a passbook.

Maggie was joined by thousands of mothers, aunts, grandmothers, and community members from Soweto, protesting on behalf of black nurses at Baragwanath. The protest resulted in the Nursing Council repealing the memorandum.

Does the Freedom Charter still represent a shared vision for South Africa today?

How can the people of 21st century South Africa, black and white, together as equals, brothers and sisters pledge themselves to strive together, sparing neither strength nor courage, until the democratic ideals of the Freedom Charter become a reality?

What prevents South Africans from standing in solidarity to ensure dignity, equality and freedom for all?

WOMEN’S MARCH TO PRETORIA

1956

In 1955, the apartheid government announced that it would issue passes to African women. In October that year 2000 female protesters marched on the Union Buildings in Pretoria (Tshwane). Another march took place on 9 August 1956 with 20 000 women carrying 100 000 signed letters which were left at the door of Prime Minister Strijdom.

They achieved this in spite of threats of violence and the anxieties of their own men. The women called out, “Wathint’bafazi, wathint’imbokodo. Strijdom uzakufa” (You strike the women, you strike the rock. Strijdom you will die). “Malibongwe! Igama lamakhosikazi” (Let the name of the women be praised!). Anti-pass protests continued throughout the country. Today, in democratic South Africa, 9 August is celebrated as Women’s Day.

WOMEN’S MARCH TO PRETORIA

WOMEN’S MARCH TO PRETORIA

Diedericks

Lillian Diedericks’s leading role in the momentous Women’s March to the Union Buildings in 1956 has been sorely neglected in accounts of the struggle against apartheid, exacerbated by a lack of archival information regarding her participation in formative women’s anti-pass events in the 1950s.

In 1954, 29-year-old Lillian, a shop steward, trade unionist, and Communist Party member became a founder of FEDSAW. A co-sponsor of the inaugural national conference on 17th April, she was part of the Eastern Cape delegation alongside Florence Matomela, Connie Njongwe and Frances Baard.

Lillian used her fluency in isiXhosa, Afrikaans, and English to bridge strategic and vital communication links with women activists from other parts of South Africa.

FEDSAW meticulously planned all aspects of the women’s march to the Union Buildings on 9th August 1956, most importantly the frontline.

Lillian formed part of the ‘second core’ of leaders of the March, alongside Amina Cachalia, Bertha Gxowa, and Violet Weinberg. This contingency was developed to ensure that FEDSAW’s leadership always led the vanguard, in the event the ‘first core’ – Rahima Moosa, Lilian Ngoyi, Helen Joseph and Sophie Williams-De Bruyn – were arrested.

Lillian and Sophie are the last two living leaders of the Women’s March for Freedom to the Union Buildings.

Hashe

In 1956, 30-year-old Viola Hashe became the first woman in South African history to hold a leading position in a national, male-dominated trade union the African Clothing Workers’ Union, where she served as Secretary General.

Having been a textile worker from a young age, Viola used her charisma and shrewd leadership skills to rise through the ranks. She was a singularly gifted orator who mobilised her fellow women workers to not only unionise for better working conditions, but to participate in mass anti-pass demonstrations, herself having been present at the Women’s March to the Union Buildings later that year.

Viola’s first act as ACWU Secretary General was to quickly amalgamate the women and men’s sections to form one cohesive South African Clothing Workers’ Union, which then joined the South African Congress of Trade Unions in 1955. Viola’s effortless weaving of her political and trade union activism was used to great effect.

Having joined the ANC during the Defiance Campaign in 1952, Viola was commended for her excellent organizational and mobilisation skills as she also rose through the party’s ranks and served on the Transvaal Provincial Executive, and later became the first woman Regional Chairperson of the West Rand region.

When she was elected Vice-President at SACTU’s Annual Conference in October 1960, Viola urged all members to keep their anti-apartheid activism strong in the face of continued state repression by saying, "We will not budge an inch. We will not be divided. The interest of the workers and the country are one."

Mompati

After moving from Vryburg to Johannesburg in 1952, Ruth Mompati joined the ANC, subsequently leading the ANCWL at the height of the anti-pass campaigns.

She decided to stop teaching because of the Bantu Education Act, and though typing courses were not offered to Black women, Ruth enrolled in a course secretly offered by an Egyptian woman in Braamfontein.

The course helped her secure a secretarial position at the law offices of Mandela and Tambo, where she became more entrenched in the activities of the ANC. Prior to the 1956 Women’s March, Ruth participated in other anti-pass campaigns, such as the marches to Baragwanath Hospital and the Native Affairs Building in Braamfontein, as well as the Transvaal Women’s March in 1955. After the formation of FEDSAW, the possibility of a nationwide women’s march to the Union Buildings in 1956 became clearer.

As one of the organisers, Ruth also assisted in collecting and counting the women’s signed petitions with Bertha Gxowa. In 1962, Walter Sisulu asked her to leave the country.

Initially protesting that she had children to look after, Ruth remembered being stunned by the following reply: “What about all these other people who have been killed, how many children did they have? ... they’re maybe men and you are a woman, but all the reason why you should go, we need people.”

Her mother agreed to stay with the children after Ruth informed her that the ANC was sending her to school for a year. Born Ruth Seichoko, she adopted the last name Mompati, the name of her firstborn son, when she went into exile, where she spent 27 years serving as part of the ANC.

Mophosho

Motsoaledi

In 1963, Caroline Motsoaledi, a mother of seven children, was arrested during a court intermission of the Rivonia Trial at the Palace of Justice.

She had left her children, the eldest a boy of ten and the youngest a baby of two months, in the temporary care of her neighbour so she could attend the proceedings in support of her husband, Elias, who was Accused Number 9, and was facing a possible death sentence.

Caroline was kept in solitary confinement without a warrant or a charge under the 90-Day Act.

Joel Joffe, who was serving as a lawyer on the Rivonia defence team, intervened and demanded that the Special Branch fetch Caroline’s mother from Middelburg to come and look after the children.

Caroline was kept in a black walled cell and taken for questioning from time to time. “... they took me to jail and left my children with my mother. I was locked away alone in a cell, I was not allowed visitors...” it remains unclear how much she knew of her husband's political activities, as she told the police nothing.

In her own capacity, she was a member of the ANCWL and would later join the Federation of Transvaal Women (FEDTRAW). She had also participated in the 1956 Women’s March on the Union Buildings.

During her time in detention, she would hear nothing about the fate of her husband or the well-being of her children. Five months would pass before Caroline was released, and by then the Rivonia Trial had ended and her husband and 7 other co-accused were serving life sentences on Robben Island and at Pretoria Central.

Thornton

In 1948, at the age of 16, and following in the footsteps of her parents who were progressive white activists, Amy Thornton (nee Reitstein) would participate in her first political campaign against the National Party (NP).

At the time she was working with the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA) and the Springbok Legion.

In 1950, as a university student, she joined a progressive youth movement, the Modern Youth Society (MYS), and in 1953 she attended a youth festival in Bucharest, Romania as an MYS representative in the South African delegation. Amy still remembers her time spent in Eastern Europe during the festival, “going behind the Iron Curtain” (travelling to countries such as Russia and Czechoslovakia), and engaging with like-minded peers from all over the world.

One exchange, with a young man from Cuba, who was part of the underground left in his country, made a particular impression. He was baffled to learn that the Communist Party in South Africa was no more simply because it had been banned.

“What do you mean, there is no communist party!?... What does that have to do with anything!?... do you think the Communist Party of Cuba was not banned?... you must have an underground party!” Amy returned to South Africa energised and ready to work for the Party’s revival.

She organised a small gathering with Modern Youth Society members and a few individuals who were members of the Communist Party in her area prior to its banning.

During the meeting she made her case, but was completely taken aback during the drive back home with Brian Bunting when he asked: “By the way, would you like to join the South African Communist Party?”

Williams-De Bruyn

At eighteen, trade unionist Sophie Williams-De Bruyn was the youngest leader of the Women’s March to the Union Buildings on 9th August 1956. She had previously worked with Raymond Mhlaba and Govan Mbeki as an executive member of the Textile Workers’ Union in Gqeberha. Following her move to Johannesburg in the early 1950s, Sophie became the full-time organiser for the Coloured People’s Congress, whose offices were in the same building as the ANC and the Transvaal Indian Congress.

This experience exposed her to other women anti-apartheid activists Helen Joseph and Lilian Ngoyi, who were on the frontline with her during the Women’s March. Sophie recalled how FEDSAW had initially planned to have a week-long march to protest the implementation of passes for black women.

However, the logistics of sourcing week-long housing and financial support for the scores of women who travelled from all over South Africa to Pretoria proved insurmountable. On the day of the march, Sophie recalled, "as the youngest person, I did not think about the danger the police posed.

The fear wasn’t prevalent in me. When I stood up there and looked at this huge multitude of women, I had a lump in my throat. The sheer thought of having pulled it off, all of us. The sheer thought of all these women managing to turn up under all odds, they made it, some even with their babies, coming from the rural areas and villages, looking like that- it was such a beautiful sight." Sophie’s youth provided her with an unshakeable confidence in the success of the march, which indeed came to pass.

How can we hold our leaders accountable, whether they are political, business, religious, or traditional leaders? How is the role that female activists play in this different to the role that male activists play?

What does the experience of being discriminated against as a woman share with experiences of being discriminated against as a LGBTQIA+ individual, or a person with disabilities, or a refugee? How do we march together on common ground?

SHARPEVILLE & THE ARMED STRUGGLE

1960

In March 1960, the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) organised peaceful protests against the pass laws. In Sharpeville south of Johannesburg, the police fired on unarmed male and female demonstrators, killing 69 and wounding 189. Many protests followed, leading to violent clashes with the police. The government declared a state of emergency and banned both the ANC and PAC, forcing them underground.

FEDSAW leaders Lilian Ngoyi, Helen Joseph and Florence Matomela were also banned. In 1961, the ANC and the South African Communist Party (SACP) decided that years of attempted negotiations, protests and strikes had no effect and that it was time to take up arms against the apartheid state. uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK) was formed as a military organisation independent from the ANC with its own command structure. POQO, the PAC’s military wing, was also formed in 1961.

SHARPEVILLE & THE ARMED STRUGGLE

SHARPEVILLE & THE ARMED STRUGGLE

Ginwala

On 21 March 1960, journalist Frene Ginwala conducted an interview with SA Indian Congress president Dr Naicker. After the interview, Dr Naicker informed Frene that Walter Sisulu was looking for her and would give her a call at 7pm.

The horrifying news of what had happened in a township called Sharpeville had already begun to spread; 69 people had been shot dead and 180 people were injured during an anti-pass protest.

When Sisulu finally spoke to Frene, he asked her to immediately leave the country. A State of Emergency was expected, and she had already been tasked to assist with Oliver Tambo’s exit into exile.

Holding a legal passport, she headed to Salisbury (now Harare), from where she made the necessary arrangements for Oliver Tambo’s exit. The ANC thereafter strategically positioned Frene in exile, where she would work to successfully establish escape routes out of South Africa.

Later, she fondly described her role at this time as being a ‘terrorist travel agent’. In 1962, Nelson Mandela paid her a surprise visit in Dar es Salaam.

Seeing him at her door, she gasped, “Now I’ve got to hide you!” – a moment she would never live down. After returning to a democratic South Africa to serve as Speaker of the National Assembly, Mandela would frequently recall this moment: “The first thing she says to me when I come out of the country and see her is, ‘I have to hide you!’ She doesn’t even welcome me!”

Head

In 1959, writer Bessie Head moved to Johannesburg from Cape Town, where she had spent a year honing her skills as the only woman reporter at The Golden Post, a sister publication of the legendary black lifestyle magazine, Drum.

It was during this time that she started corresponding with American poet Langston Hughes, telling him that her writing sprung from “such a feeling of desperation, absolute frustration and a deep sense of isolation, of not belonging”.

In Johannesburg Bessie joined The Home Post, a supplement of The Golden Post, and soon became politicised following exposure to various anti-apartheid campaigns. Socialising with the ‘Drum Boys’ – the famed investigative journalists Can Themba, Todd Matshikiza and Lewis Nkosi – also inspired her to become more active in the struggle.

Bessie became a member of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) in 1960, inspired by the organisation’s unyielding militancy and by PAC president Robert Sobukwe.

Following the Sharpeville Massacre in March 1960, Bessie was arrested for her political activities – collecting money for women and children who had lost breadwinners due to the massacre, and sharing ‘seditious material’. Detention was especially traumatic for Bessie. Under pressure from the police she revealed information about the PAC, which she considered a betrayal of the movement, and led to her attempting suicide after her release.

In a letter to Sobukwe during his imprisonment on Robben Island she said, “I found in many ways that I was not basically a politician, though circumstances in South Africa make one some kind of political thinker…my first book was really to free myself of a sort of prison and to look more deeply at Africa’s destiny which I hope will be the destiny of mankind – a wealth of humanity and a richness of culture, without the dark taints of class arrogance and power-mongering."

Kasrils

Eleanor Kasrils’ escape from detention and the clutches of the Security Branch in 1963 could easily provide the plot for a thrilling Cold War-era spy film. Eleanor, an uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK) and SACP member living in Durban, used her mother’s bookstore, Griggs, as a front to discreetly share confidential information with her comrades underground.

However, Eleanor’s luck ran out when she was detained under the 90-Day Detention Act by the Security Branch on 19 August 1963. This Act allowed the apartheid police to enter a far more brutal and intensive phase of repression. In protest against her unlawful detention and being physically assaulted by Lieutenant Grobler during interrogations, Eleanor began a hunger strike.

This led to her transfer to Fort Napier Psychiatric Hospital in Pietermaritzburg, as the authorities were concerned for her mental health and that she might become the first white person to die in detention. Eleanor later recounted to her husband, fellow MK cadre Ronnie, that “as mentally disturbed as these inmates were, they were nowhere near as mad as Grobler and most of the Special Branch – a gang of sadistic brutes and torturers in the service of an insane government”.

Assisted by Precious, a Black nurse at Fort Napier, who helped “any umlungu who is with us and against the Boers”, Eleanor ingeniously escaped from the hospital on 22 September 1964. She slipped out the back door Precious had left open, changed into staff clothes, and simply walked out of the main gate! Hours later, Pietermaritzburg came to a standstill as the police tried to find her, but by then Eleanor was disguised as a schoolboy, and, after cutting and dyeing her hair, was making her way to Johannesburg in the company of fellow activist and student Rob Anderson.

Magona

“The value in my story is the authenticity of my voice, of me bearing witness. This is my truth that I write of what matters to me…” Sindiwe Magona recalls her lived experiences and those of others during apartheid South Africa through her literary works.

In 1948, at the age of 5, Sindiwe moved from the Transkei to live with her parents in the Blouvlei Township in Cape Town. Although the family had moved to an urban area, the ‘promise’ of a new horizon was in fact simply the promise of worsening conditions. As all Africans in urban areas, Sindiwe and her family were designated ‘Temporary Sojourners’ or ‘Non-Citizens’, a fundamental challenge to their humanity and that of millions of Black South Africans. In her writing, Sindiwe tells of her experience of extreme poverty and of making a living as a domestic worker while she schooled herself through distance learning. She would go on to be a teacher, mother, wife and community leader, complete post-graduate studies and spend two decades in civil service with the United Nations. Living through the trauma of constant forced evictions and many other restrictions from a young age compelled Sindiwe to record and tell these stories for future generations. “I experienced incredible anger about others writing about us, I asked myself, “How dare they write about you?” I told myself that shouldn’t stop me from writing about myself…there is value in those like me writing about our experiences, who did not study apartheid but lived it.”

Sobukwe

The letters exchanged between Zondeni “Zodwa” and her husband Robert Sobukwe reveal that the separation caused by his imprisonment was long, difficult, and lonely for both. They had married on 6 June 1954, in a traditional affair where Robert paid lobola to the Mathe family.

Veronica resumed work in between having the children, doing general district nursing in Soweto, and says: "It was a happy family life. He often arrived home with a paper-carrier of food he had bought. He loved being with the children. He spent a lot of time with them. He told them a lot of stories, Xhosa stories."

In 1960, Robert was sentenced to three years at Pretoria Prison after leading a Pan African Congress anti-pass march in Sharpeville when the apartheid police killed 69 unarmed supporters. In 1963, he wrote to Veronica from Pretoria Gaol, “I thought I should take this opportunity to tell you how just how much your courage and love have meant to me during all these years of imprisonment…it is quite possible that after a time I may forget what you suffered on my behalf.That is why I want you to have this written testimony from me so that we both of us can go back to it in future. I just wish to say, Child, that you have been a magnificent wife and mother. You have been everything I could have wished my wife to be. And I mean that Little Woman. And the children, too, will agree with me!”

Tambo

In 1958, Adelaide Tambo was apprehensive about the possibility of leaving South Africa to continue the struggle against apartheid abroad. Her husband Oliver, returning from an Africa Day rally in Alexandra, informed her that the ANC executive leadership had instructed him to leave the country with his family to garner international support against apartheid South Africa’s policies.

The leadership realised that his family had to accompany him for Oliver to truly commit to his mission overseas. However, the tragic events of the Sharpeville Massacre on 21 March 1960 left the Tambo family in disarray as Oliver was immediately ordered to leave the country to evade arrest.

Months later, arrangements were made for Adelaide and their children, Dali and Tselane, to join Oliver in exile. She recalled suffering from anxiety about leaving South Africa for the first time and the uncertainty of a new beginning in a foreign land, as "we were in the struggle, there was nothing romantic or glamourous about it."" Adelaide and the children travelled to Swaziland, Botswana, and Ghana before reuniting with Oliver in London in September 1960.

However, the family would only see Oliver twice a year due to his extensive travelling to speaking engagements around the world. Leaving her as the family’s sole breadwinner in exile, Adelaide supported the family by working double-shifts as a nurse. Additionally, her commitment to the struggle in South Africa never wavered as Adelaide continued to work with international solidarity organisations and offered their Muswell Hill home as sanctuary to other South African families in exile.

The Tambo family returned to South Africa on 6 August 1990, after spending 30 years in exile. Upon arriving at Johannesburg International Airport, Adelaide laden with twelve large suitcases, simply remarked, "I am not waiting one minute! This is my luggage; I have been out of the country for 30 years! I am going in- arrest me if you want!", to which the bemused airport official responded, "All right ma’am, gaan verby (pass by)."

Turok

Mary Turok, a member of the banned SACP and COD, was jailed for illegal activities under the 90-Day Detention Act in 1962. Mary, with fellow underground cell members Pixie Benjamin, Ann Nicholson and Molly Anderson, went on a secret mission in Johannesburg to put up posters protesting the continued banning of the ANC and the PAC.

Unbeknownst to them, another cell member had informed the apartheid police of the planned activity, and the women were caught in the act, detained at the Fort Women’s Prison, and moved to Pietersburg Prison for three months. The prisoners, separated by race, were tasked with crocheting and, ironically, sewing policemen’s uniforms, which Mary thought ‘an eye-opener’. At that time, her husband Ben, Treason Trialist, lecturer and underground SACP leader, was sentenced to a three-year term at Pretoria Central under the Explosives Act. This left their three young children in the care of their maternal grandmother and friends. A cruel consequence of anti-apartheid activism was for many families the separation of parents from their children for long periods of time. Mary, Ben and the children reunited in 1965, a year after the Rivonia Trialists were sentenced to life imprisonment. However, when SACTU and COD president Pieter Beyleveld turned state witness at Bram Fischer’s first trial in 1964, he revealed the names of 80 other wanted communist associates. Rumours of Mary’s imminent arrest in 1966 prompted the family to secretly leave South Africa for Nairobi and settle in Dar es Salaam, where Mary worked as a doctor’s assistant at Muhimbili Hospital until they moved to London in 1969.

When dialogue breaks down, people often experience threats of violence and economic manipulation. How do we maintain productive and meaningful dialogue with those who disagree with us?

How can we translate that dialogue into action so that the patience of those with the most urgent needs does not have to be endless?

LILIESLEAF RAID & RIVONIA TRIAL

1963 - 1964

MK’s initial acts of sabotage were directed at symbolic targets, not at people. Some felt this was not enough as the apartheid government’s responses were becoming more brutal. A more radical strategy of guerrilla warfare, called Operation Mayibuye, was drafted by a group of MK leaders. It was being discussed at Liliesleaf on 11 July 1963 when the police raided and arrested the leaders.

Nelson Mandela, who was already in prison for leaving South Africa illegally in 1962 (seeking support for MK from African leaders), joined nine other accused as Accused Number One in the Rivonia Trial. Women associated with these men were detained and interrogated, including Albertina Sisulu, Caroline Motsoaledi, Ruth First, Hazel Goldreich, Esme Goldberg, Enith Khopane, Maureen Kreel and AnnMarie Wolpe.

LILIESLEAF RAID & RIVONIA TRIAL

LILIESLEAF RAID & RIVONIA TRIAL

Fischer

Molly Fischer’s role in the struggle against apartheid is often overshadowed by that of her better-known husband, Bram Fischer, Rivonia defence lawyer and Communist Party leader. Molly Krige hailed from a respected Afrikaner family.

Her father had served alongside General Jan Smuts during World War I, and Smuts would later marry Molly’s paternal aunt Isie. Molly’s marriage to Bram in 1937 strengthened her political consciousness and entrenched her abhorrence of apartheid.

She confronted any forms of racism she encountered, risking ostracization by her own people for her ‘radical’ views. Ruth Rice, Molly and Bram’s eldest daughter, recounted that Molly was ‘feisty’ in her activism and that ‘she would stand up and fight wherever she saw petty racism. Bram introduced her to notable women activists like Albertina Sisulu and Winnie Madikizela-Mandela.

Molly and Albertina grew so close that Molly provided the Sisulu family with financial and emotional support during the Rivonia Trial in 1964. Molly’s tragic death in a car accident en route to daughter Ilse Wilson’s 21st birthday party in Cape Town, the day after the sentencing of the Rivonia Trialists, left many activists, including Albertina and Hilda Bernstein, bereft.

Albertina recounted that " Molly’s death was a terrible blow to a family and community already traumatised by relentless police persecution". After her cremation, Ruth and Ilse presented Albertina with the three suitcases Molly had packed for the trip. She thought this moment profoundly moving as it was " a symbolic gesture" that acknowledged their mother’s passing and how Albertina was now the only mother figure left for them.

Hodgson

In 1960, days before the State of Emergency was declared, Rica Hodgson answered a mysterious telephone call from a man who wanted to speak to Jack, who was out attending a meeting. Jack interpreted the coded message as a ‘mass arrests’ signal, and after warning his comrades of the impending upheaval, went into hiding in Swaziland, leaving her alone in South Africa.

However, when the police knocked on the door of the Hodgsons’ fourth floor flat in Hillbrow, they only held a warrant for Rica’s arrest, and she was detained for three months. Jack, upon hearing of her detainment, forever regretted leaving Rica, vowed never to leave her side, and returned to South Africa to participate in the armed struggle.

In 1961, Rica and Jack defied the apartheid government by clandestinely mixing the first MK explosives in their Hillbrow kitchen, which Rica jokingly referred to as ‘a veritable bomb factory’. These explosives were used in sabotage campaigns on 16 December 1961, the day MK’s presence in South Africa was formally announced. Jack, as part of MK’s High Command, worked closely with Nelson Mandela in testing the explosives, training new cadres, and often visited Liliesleaf, the liberation movement’s underground headquarters.

Months before the Liliesleaf Raid on 11 July 1963, Rica and Jack were instructed to leave South Africa. They illegally crossed into Lobatse, Bechuanaland (now Botswana), where they planned to establish an MK transit base. At the time, the country was a British protectorate, and the Hodgsons possessed British passports.

However, the British authorities declared Rica and Jack prohibited immigrants in September 1963. In a vulnerable position, the apartheid government unsuccessfully attempted to kidnap the Hodgsons back to South Africa. Fearing for their safety, the British authorities deported Rica and Jack to London, where they continued their anti-apartheid activism, with Rica working for the British Defence and Aid Fund as a fundraiser.

Mbeki

In South Africa’s collective historical memory, Epainette Mbeki’s contribution to the liberation struggle is often subsumed by the legacies of her husband, Govan and her son, Thabo. In truth, the Mbeki men could not have wholly given themselves to the struggle were it not for her unshakable commitment to the praxis of socialist principles of the community over the self.

For Epainette, the struggle against apartheid was firmly rooted in mobilising resistance in the rural areas and uplifting women to become financially independent through education and cooperative community activism. Recruited by trade unionist Bettie du Toit, eighteen-year old teacher Epainette joined the CPSA in 1938 and was impressed by the practical work done to empower its black members through literacy and political education classes.

Following Josie Mpama, Epainette was among the first black women to join the party. Epainette moved to Mbewuleni, near Dutywa with Govan in 1940, where they founded a cooperative store to support their community in a way that would not make them dependent on the apartheid government for assistance. By 1960, Epainette and Govan had been living separate lives for a nearly a decade.

Govan had left the Eastern Cape and had been hiding with the rest of the high command of the ANC’s armed wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), at Liliesleaf Farm in Rivonia, outside Johannesburg. The Rivonia Trial in 1964 was a crushing blow for Epainette as Govan was sentenced to life imprisonment. They were reunited in 1990, 26 years later.

Mlangeni

When June and Andrew Mlangeni decided to formally join the ANC in 1954, they were both aware of the personal risks of actively opposing apartheid. Andrew recalled saying to June, "My dear, we have to prepare ourselves as people engaged in the struggle.We know from the history of other struggles that when people go to prison, they go for a long time…"" These prophetic words would come true, years later on 12 June 1964, the last day of the Rivonia Trial.

Andrew and nine other ANC leaders were charged with 222 counts of sabotage designed to overthrow the apartheid government, after the police raided Liliesleaf Farm on 11 July 1963.

In an unprecedented move, the apartheid regime broadcast the court proceedings, and the world anxiously awaited the verdict to be passed on eight of the ten accused, with the threat of death sentences looming over their heads.

Though the death penalty was avoided, it was still difficult for June to witness Andrew and her ANC leaders being sentenced to life imprisonment. Albertina Sisulu, who was close friends with June, recalled that when Judge Quartus de Wet pronounced the verdict, the spectators had not heard the sentence. June desperately shouted, "how long, how long?", "Life", Andrew solemnly replied.

June’s first trip to visit Andrew on Robben Island was arduous. She recalled how the journey to Cape Town from Johannesburg took two nights by train; at the station, June had to walk to Cape Town Harbour to catch a ferry to the prison.

Once there, June and Andrew had to shout across a fence to hear each other, which she found greatly upsetting. She recalled, "I didn’t want to show him I was hurt, I wanted him to feel that I wasn’t worried, although really, I was very much hurt to see him the way he was, dressed (in a jacket, khaki shorts, and sandals) in that weather. I was hurt to see him standing there like that."

Sisulu

The ANC’s decision to move towards armed struggle resulted in long periods of separation for Albertina Sisulu’s family. Albertina, a nurse since 1946, was the family’s sole breadwinner and had to continue working while her husband Walter organised the ANC’s underground structures after the organisation was banned in 1960. As leading figures in the ANC, they endured constant police raids and harassment at their Orlando West home.